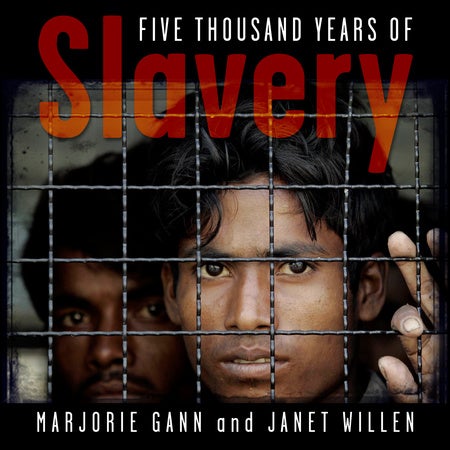

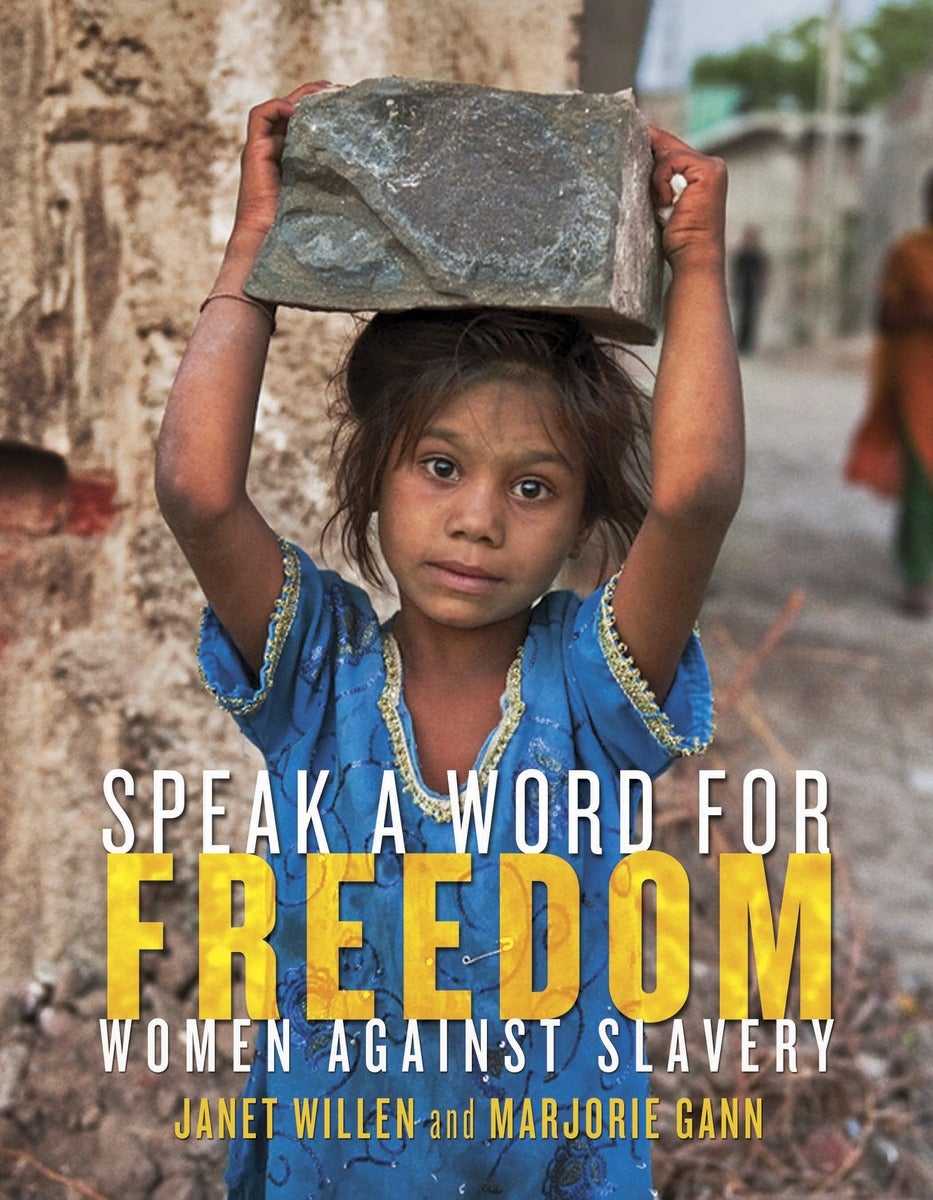

In honor of Women’s History Month, we have a special guest post from Marjorie Gann and Janet Willen, authors of Speak a Word for Freedom and Five Thousand Years of Slavery. Read on to learn more about some incredible women who fought against slavery:

Marjorie and Janet: Our first book, Five Thousand Years of Slavery, tells the story of world slavery from ancient times to the present. While doing our research, we discovered that women played a major role in the campaign against slavery. It was their first political battle, even before they fought for the right to vote. We were so intrigued that we decided to devote our second book to their involvement.

Speak a Word for Freedom tells the story of fourteen women who have fought against slavery in different regions of the world over the past 250 years.

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’d like to introduce you to four of these remarkable women:

Mum Bett was a slave in the home of John and Hannah Ashley in Sheffield, Massachusetts. One day while Bett and her sister were in the kitchen, Mrs. Ashley, a quick-tempered woman, lifted a hot kitchen shovel from the stove and aimed it at Bett’s sister. To protect her, Bett jumped in front of the girl, catching the blow on her arm and suffering a severe wound.

As a slave, Bett had overheard many prominent guests talk around Mr. Ashley’s table. One of them, Theodore Sedgwick, described Massachusetts’ new constitution, which said all people were “born free and equal.” After being assaulted, Bett went to see him and asked if the law could free her. If all people are born free and equal, she asked, shouldn’t she be?

Sedgwick agreed to take her case to court. On August 21, 1781, Sedgwick told the jury there was no law establishing slavery and that the Massachusetts state constitution made slavery illegal because it said all people were “born free and equal.”

Mr. Ashley claimed she was a slave by law.

Bett’s argument won, and she and an enslaved man named Brom, who joined the case with her, were freed. To recognize her status as a free woman, Bett changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman. Mum Bett’s anti-slavery case was the first to cite the state constitution but not the last.

Elizabeth Heyrick, a white woman in England, became a leader in its abolition movement. As a convert to the Quaker religion, she fully adopted its message of equality regardless of race, sex, or social class, and refused to remain silent in the face of injustice.

By 1808, Britain had ended the slave trade that brought captured Africans to its colonies, but slavery continued to thrive in its Caribbean islands. Slaves produced the sugar that made British plantation owners rich.

Heyrick believed slaves had waited too long for their freedom. In 1823, she used the tool she had at hand – a pen – to protest the injustice. Printed pamphlets were the social media of her day, and she wrote seven to protest slavery.

In her first anti-slavery pamphlet, she called slavery a national disgrace and announced something new for the time: a boycott of slave-produced sugar. “When there is no longer a market for the productions of slave labor, then, and not till then, will the slaves be emancipated.” She knew that both women and men would be suspicious of a pamphlet written by a woman, so she didn’t sign her name.

The abolitionist group active in Britain was for men only, so she helped to form one for women. The men’s group called for the gradual abolition of slavery, but women demanded it end immediately.

Heyrick’s group was so popular that it raised enough money to contribute to the men’s group. In 1830, though, they said they would not give any more money to the men until they, too, called for an immediate end to slavery. Seven weeks later the men did.

In 1833 the event Heyrick had long hoped for arrived, passage of the Slavery Abolition Act, ending slavery in the British colonies. Heyrick had died two years earlier.

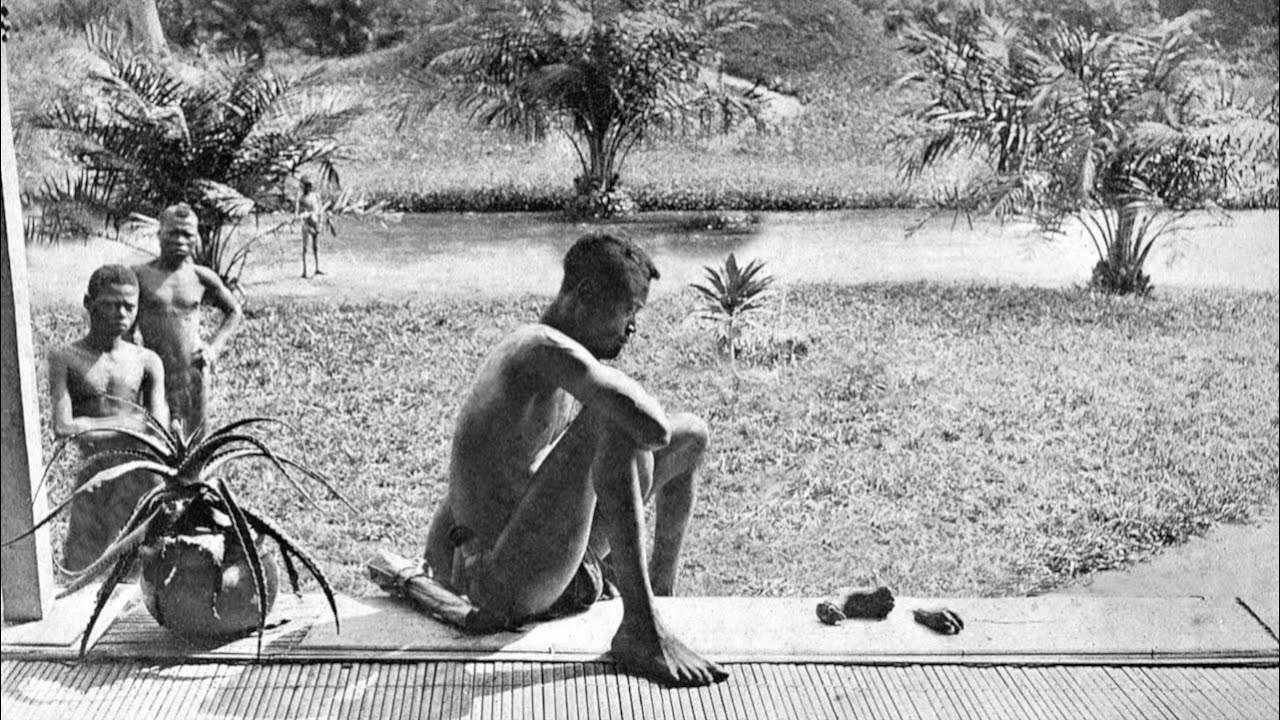

When British missionary Alice Seeley Harris arrived in the Congo Free State with her husband, John, in 1889, they had one goal: to convert the native people to Christianity. But the atrocities they witnessed upended their mission.

The Congo Free State was created in Africa in 1885 by King Leopold II of Belgium to exploit the land for its natural resources, especially rubber, and to enrich himself. Agents of the king forced the natives into the bush to harvest rubber.

One Sunday morning, a man named Nsala arrived at the Harrises’ mission with what looked like a bundle of leaves in his hand. Alice opened it to see the severed hand and foot of his daughter, shown in this picture. This atrocity was a warning to Nsala and other rubber workers that they must meet their quotas for the Belgians or suffer mutilation.

Knowing that a picture is worth a thousand words, Alice, a skilled photographer, graphically documented the brutality in photographs published in reports and pamphlets sent to England. On visits there, the Harrises gave public lectures illustrated with Alice’s photographs. The steady barrage of negative publicity incensed the public against King Leopold. By 1908, the disgraced monarch was forced to turn the governance of the Congo over to the Belgian government.

“I was sold like a goat,” says Hadijatou Mani, describing her sale as a slave at age twelve to a forty-six-year-old man in Niger in West Africa. She was known as a “fifth wife,” but had none of the rights or privileges of a wife under Islamic law. Instead, she was forced to work in her master’s house and fields, obey him in all things, and submit to beatings and humiliation.

Fortunately for Mani, a local antislavery organization, Timidria, was working to end the practice of slavery in Niger, where it was illegal but still widespread. With help from Anti-Slavery International in Britain, they sued the nation of Niger in a Western African regional court.

Although Mani was afraid to speak, her lawyers told her to look at the woman judge and talk to her “the way you do to us.” Mani gave a heartfelt account of her years of abuse and suffering. The judges awarded her damages from the government of Niger for its failure to protect one of its citizens against enslavement. This was a victory not only for Mani but also for others facing the same degradation in Niger.

In March 2009 this woman, who had never left her country, flown on a plane, or felt a cold breeze, traveled to Washington, DC, to receive the International Women of Courage Award from then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who praised her “inspiring courage in challenging an entrenched system of caste-based slavery.”

Each of the women in Speak a Word took a courageous step. Though not all won awards, they have all won our admiration for never giving up in the fight for justice.

Want to learn more about these amazing women and many others? Check out Janet and Marjorie’s books!

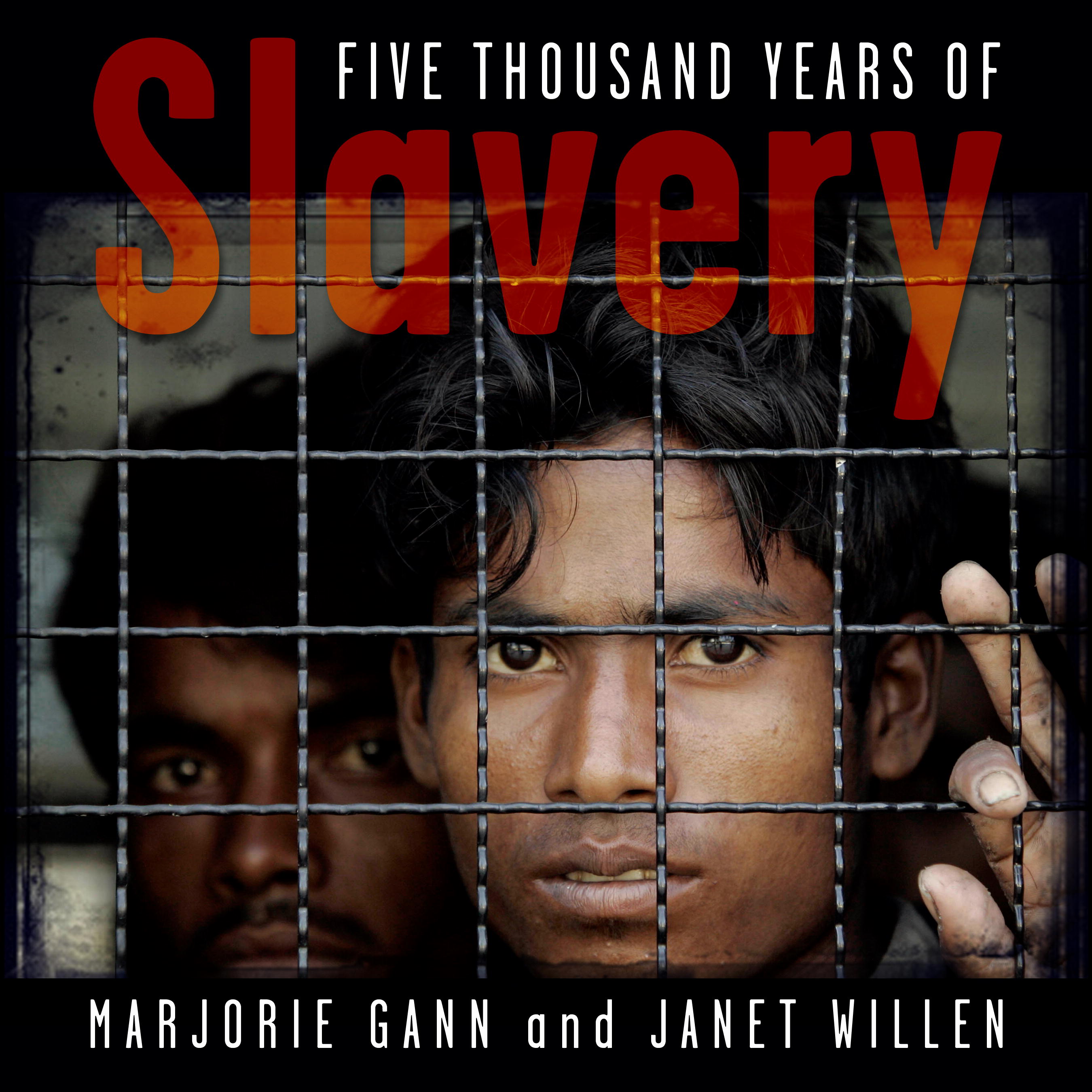

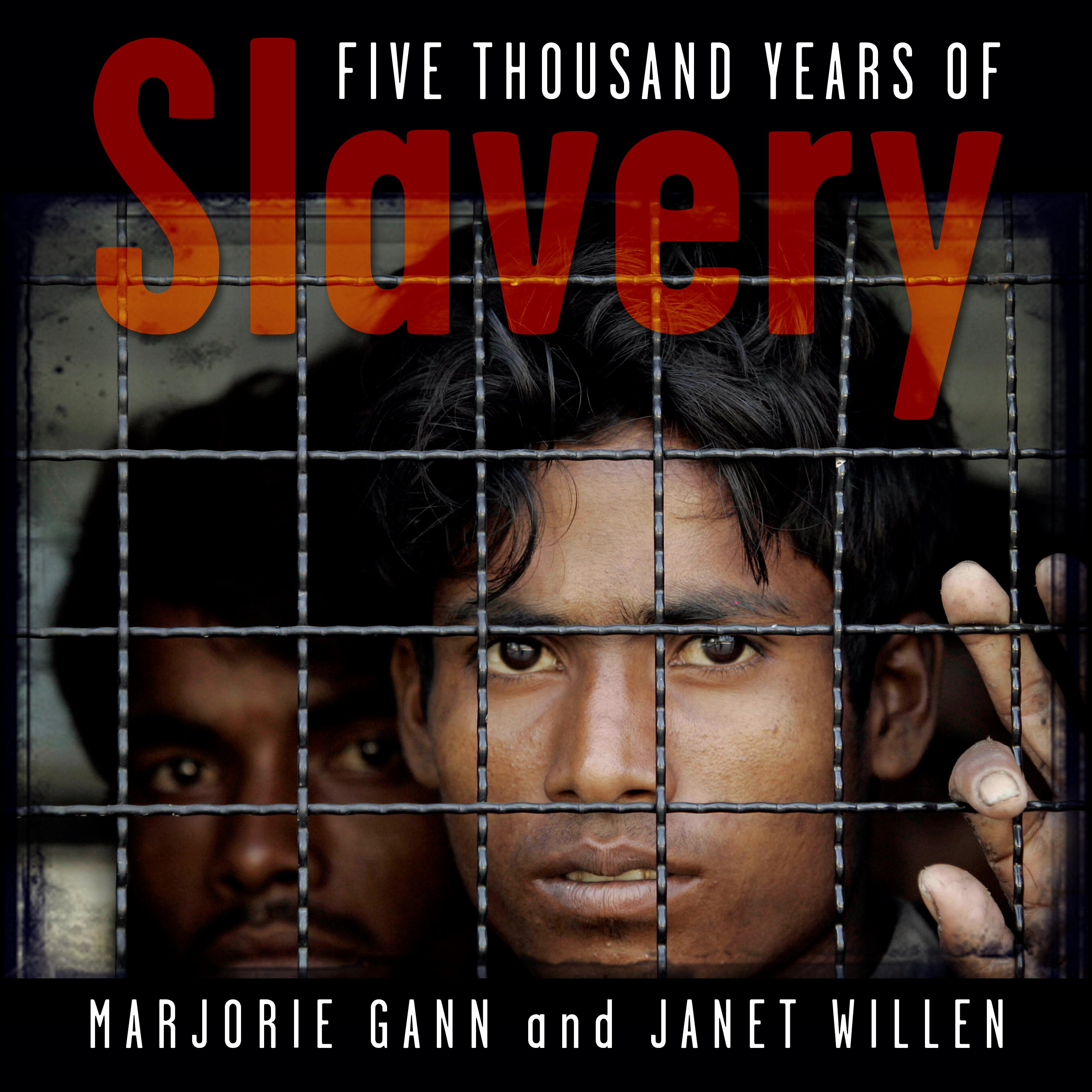

Five Thousand Years of Slavery

Five Thousand Years of Slavery

By Marjorie Gann and Janet Willen

176 Pages | Ages 10+ | Ebook

ISBN 9781770491519 | Tundra Books

When they were too impoverished to raise their families, ancient Sumerians sold their children into bondage. Slave women in Rome faced never-ending household drudgery. The ninth-century Zanj were transported from East Africa to work the salt marshes of Iraq. Cotton pickers worked under terrible duress in the American South. Ancient history? Tragically, no. In our time, slavery wears many faces. James Kofi Annan’s parents in Ghana sold him because they could not feed him. Beatrice Fernando had to work almost around the clock in Lebanon. Julia Gabriel was trafficked from Arizona to the cucumber fields of South Carolina. Five Thousand Years of Slavery provides the suspense and emotional engagement of a great novel. It is an excellent resource with its comprehensive historical narrative, firsthand accounts, maps, archival photos, paintings and posters, an index, and suggestions for further reading. Much more than a reference work, it is a brilliant exploration of the worst – and the best – in human society.

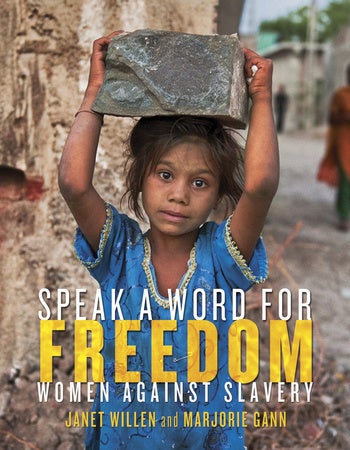

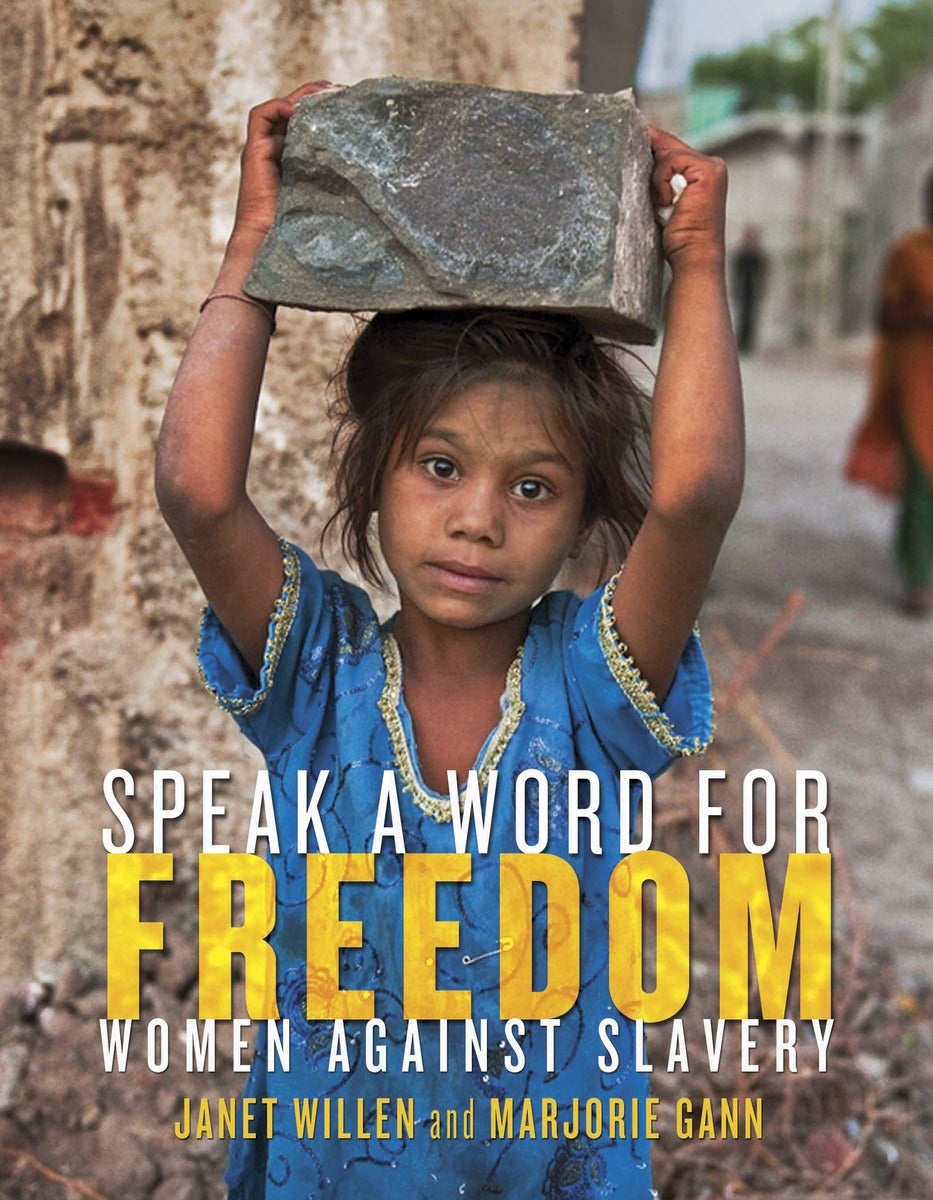

Speak a Word for Freedom

Speak a Word for Freedom

Women against Slavery

By Marjorie Gann and Janet Willen

216 Pages | Ages 12+ | Hardcover

ISBN 9781770496514 | Tundra Books

From the early days of the antislavery movement, when political action by women was frowned upon, British and American women were tireless and uncompromising campaigners. Without their efforts, emancipation would have taken much longer. And the commitment of today’s women, who fight against human trafficking and child slavery, descends directly from that of the early female activists. Speak a Word for Freedom: Women against Slavery tells the story of fourteen of these women. Meet Alice Seeley Harris, the British missionary whose graphic photographs of mutilated Congolese rubber slaves in 1904 galvanized a nation; Hadijatou Mani, the woman from Niger who successfully sued her own government in 2008 for failing to protect her from slavery, as well as Elizabeth Freeman, Elizabeth Heyrick, Ellen Craft, Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frances Anne Kemble, Kathleen Simon, Fredericka Martin, Timea Nagy, Micheline Slattery, Sheila Roseau and Nina Smith. With photographs, source notes, and index.